Deinotherium

7474Deinotherium (Deinotherium Kaup, 1829)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Deinotheriidae

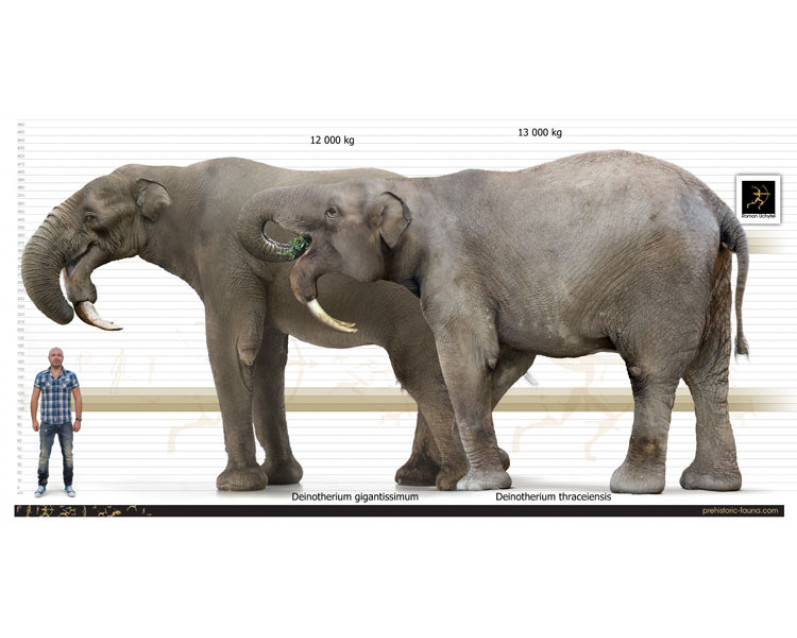

Dimensions: length - 7 m, height - 3,5 - 4,1 m, weight - 8 000 - 13 000 kg

Temporal range: lived during the Late Miocene until the genus' extinction during the Early Pleistocene (Africa, Europe, and Asia)

Species: † Deinotherium bozasi (Arambourg, 1934)

† Deinotherium giganteum (Kaup, 1829)

† Deinotherium indicum (Falconer, 1845)

† Deinotherium proavum

† Deinotherium thraceiensis sp. nov. (Kovachev, 1964)

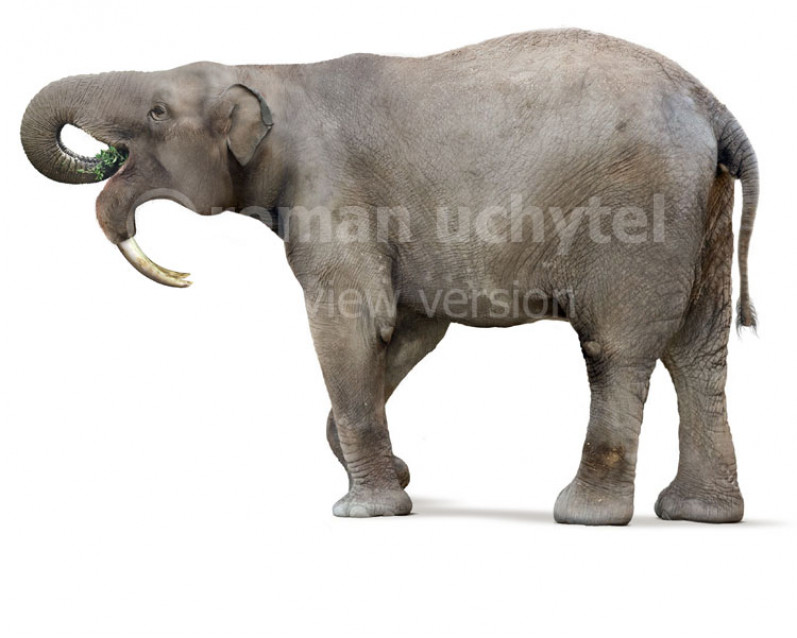

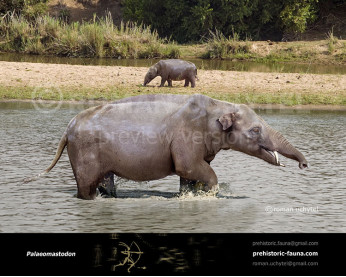

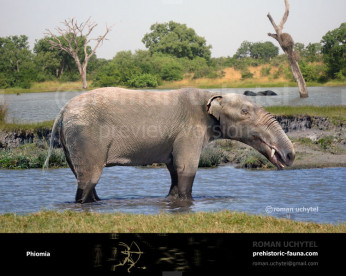

Deinotherium was one of the most largest land animals of the Late Miocene-Early Pleistocene. The length of the body from different species ranged from 3.5-7 metres, and the height at the shoulders reaching 3-5 m (average 3.5-4 m), and weight can be up 12 000 kg. On the surface they resembled modern elephants but the proportions differed from them. Typically, the trunk was relatively hollow, shortened and remained at high, but massive columnar limbs, indicating they are somewhat different than other Proboscidea functions.

The body is rather short on a long tail. Compared with other Proboscidea Deinotherium had a rather long and flexible neck, which allowed the structure to lift and bend its head and turn it from side to side. This structure is associated with the ability to lift its head up and make its tusks work. In the normal position of the head, it was positioned horizontally and was in the same place with the neck of the animal. It was perhaps one of the most biggest hairless elephants of all time. Compared with the massive body, the skull of Deinotherium was relatively small, with the characteristic tusks in the lower jaw. Projecting from the jaw of the tusks could reach up to 1 m, but was usually smaller. It is not excluded that the tusks were playing an important role in the social life of these animals, acting, for example, as a tournament of arms of males in the breeding season but were used for getting food. Animals could bend down and break off branches from trees, as well as strip bark from tree trunks for eating.

Deinotherium (Deinotherium Kaup, 1829)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Deinotheriidae

Dimensions: length - 7 m, height - 3,5 - 4,1 m, weight - 8 000 - 13 000 kg

Temporal range: lived during the Late Miocene until the genus' extinction during the Early Pleistocene (Africa, Europe, and Asia)

Species: † Deinotherium bozasi (Arambourg, 1934)

† Deinotherium giganteum (Kaup, 1829)

† Deinotherium indicum (Falconer, 1845)

† Deinotherium proavum

† Deinotherium thraceiensis sp. nov. (Kovachev, 1964)

Deinotherium was one of the most largest land animals of the Late Miocene-Early Pleistocene. The length of the body from different species ranged from 3.5-7 metres, and the height at the shoulders reaching 3-5 m (average 3.5-4 m), and weight can be up 12 000 kg. On the surface they resembled modern elephants but the proportions differed from them. Typically, the trunk was relatively hollow, shortened and remained at high, but massive columnar limbs, indicating they are somewhat different than other Proboscidea functions.

The body is rather short on a long tail. Compared with other Proboscidea Deinotherium had a rather long and flexible neck, which allowed the structure to lift and bend its head and turn it from side to side. This structure is associated with the ability to lift its head up and make its tusks work. In the normal position of the head, it was positioned horizontally and was in the same place with the neck of the animal. It was perhaps one of the most biggest hairless elephants of all time. Compared with the massive body, the skull of Deinotherium was relatively small, with the characteristic tusks in the lower jaw. Projecting from the jaw of the tusks could reach up to 1 m, but was usually smaller. It is not excluded that the tusks were playing an important role in the social life of these animals, acting, for example, as a tournament of arms of males in the breeding season but were used for getting food. Animals could bend down and break off branches from trees, as well as strip bark from tree trunks for eating.