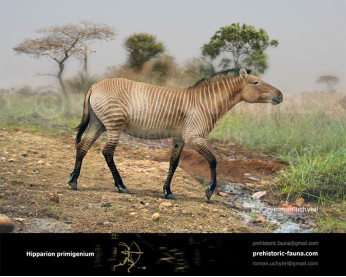

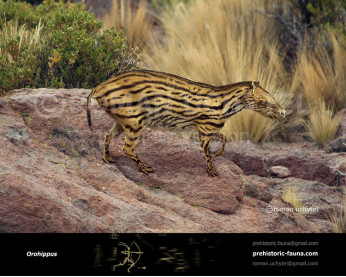

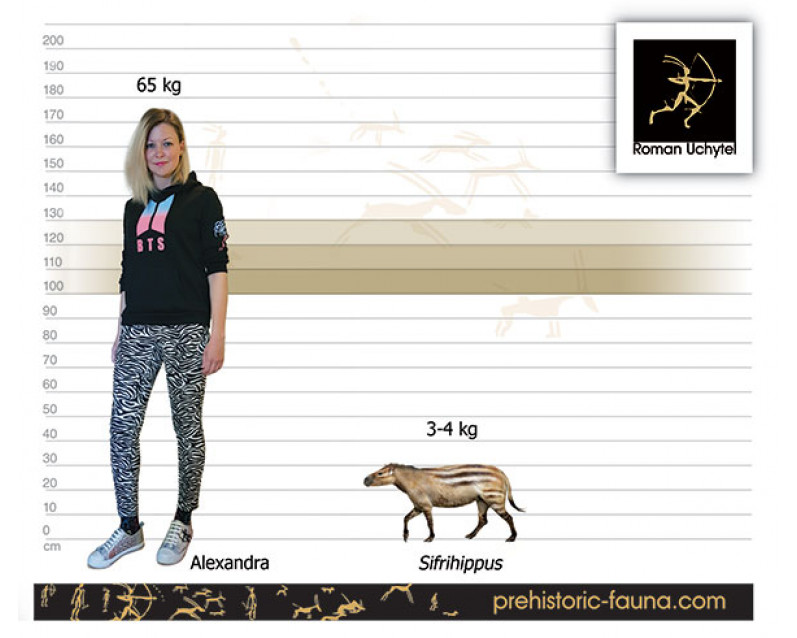

Sifrihippus

477477

During what's known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, about 56 million years ago, a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere and oceans boosted average global temperatures by about 5.5 degrees Celsius over 175,000 years. Mammals responded to this climate change by shrinking, with about one-third of species getting smaller.

Now, new research reveals that these changes occurred in lockstep with temperature fluctuations during the period. The earliest-known horse Sifrhippus started out this period as a bit of a pipsqueak: The animals weighed only about 5.6 kilograms on average, about the size of a miniature schnauzer.

But by 130,000 years into the PETM, Sifrihippus had shrunk down to only about 3.9 kg, the size of a small housecat. These humble horses then experienced a size rebound, bulking up to about 7 kg in the last 45,000 years of this warm period, putting them on par with the average bichon frise.

Measurements of horses' teeth found in the area suggested a distinct pattern of shrinking and growing body size over the PETM time period.

The researchers then analyzed the oxygen isotopes (atoms of the same element with different masses) in the horse teeth, which serve as markers of local temperatures at the time the horses died. They found that temperatures perfectly matched up with size measurements. The hotter it got, the smaller the horses. Other factors, including aridity and carbon dioxide concentration, did not match up as well.

This, for the first time, tells us that temperature is what's driving the body size evolution for these horses.

The findings fit with what is known about modern-day mammals and birds, which are generally smaller near the equator. This may be because smaller size helps animals regulate their body temperatures in the heat, or perhaps because of the availability of food sources. Much of the land near the equator is arid, and food sources are slim.

Оплата

У Вас є кілька зручних способів купівлі зображення: кредитна чи дебетова картка Visa, Mastercard, Maestro; PayPal або банківський переказ

During what's known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, about 56 million years ago, a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere and oceans boosted average global temperatures by about 5.5 degrees Celsius over 175,000 years. Mammals responded to this climate change by shrinking, with about one-third of species getting smaller.

Now, new research reveals that these changes occurred in lockstep with temperature fluctuations during the period. The earliest-known horse Sifrhippus started out this period as a bit of a pipsqueak: The animals weighed only about 5.6 kilograms on average, about the size of a miniature schnauzer.

But by 130,000 years into the PETM, Sifrihippus had shrunk down to only about 3.9 kg, the size of a small housecat. These humble horses then experienced a size rebound, bulking up to about 7 kg in the last 45,000 years of this warm period, putting them on par with the average bichon frise.

Measurements of horses' teeth found in the area suggested a distinct pattern of shrinking and growing body size over the PETM time period.

The researchers then analyzed the oxygen isotopes (atoms of the same element with different masses) in the horse teeth, which serve as markers of local temperatures at the time the horses died. They found that temperatures perfectly matched up with size measurements. The hotter it got, the smaller the horses. Other factors, including aridity and carbon dioxide concentration, did not match up as well.

This, for the first time, tells us that temperature is what's driving the body size evolution for these horses.

The findings fit with what is known about modern-day mammals and birds, which are generally smaller near the equator. This may be because smaller size helps animals regulate their body temperatures in the heat, or perhaps because of the availability of food sources. Much of the land near the equator is arid, and food sources are slim.

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)