Lestodon

519519

Lestodon (†Lestodon (Gervais 1855))

Order: Pilosa

Family: †Mylodontidae

Temporal range: during the Early Pliocene-Pleistocene (South America, ~5.332–0.012 Ma)

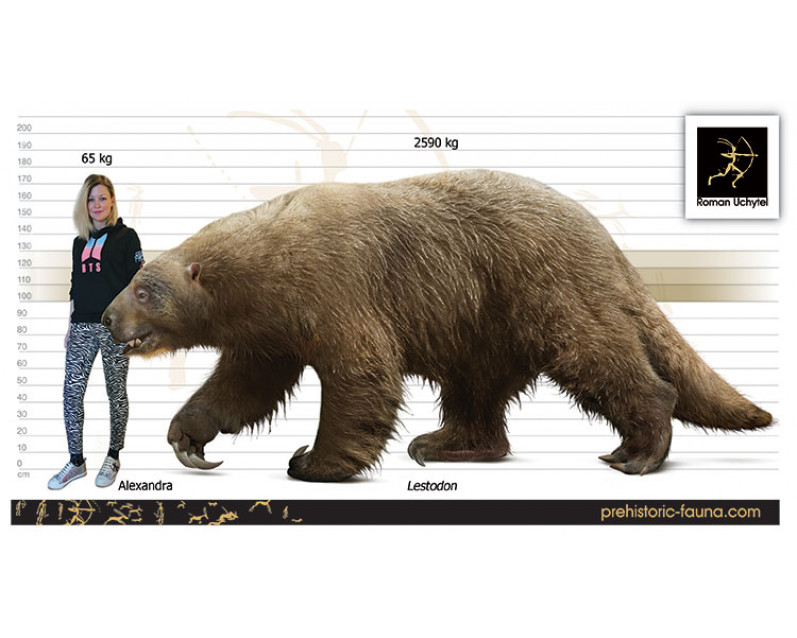

Dimensions: length -4,6 m, height - 170 сm, weight - 2590 kg

A typical representative: † Lestodon armatus (Gervais 1855)

Lestodon is an extinct genus of megafaunal ground sloth from South America during the Pliocene to Pleistocene periods. Its fossil remains have been found in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Brazil. It was a herbivore and primarily fed on the grasses on the South American plains and is thought to perhaps have used its semi-bipedal stance to obtain foliage from trees.

The skeleton morphologically reflects its evolutionary history as well as its daily activities. The skull is two to three orders of magnitude larger than that of living species of sloth, but the muzzle itself shows highly positive allometry to the size of the skull in comparison to modern sloths and even other megafauna of the same order Pilosa.

L. armatus had a large, blunt, and square mandible well adapted for foliage consumption. Its muzzle and dentition show a significant adaptation to this diet. The shape of the muzzle aided the ground sloth in the grazing necessary to sustain the metabolic activity of its large body; square, flat muzzles are associated with bulk feeders while pointed snouts are adaptive features of precision eaters, like the long sloping snout of modern anteaters, which are also in the same class Xenarthra. To sustain its caloric needs with only plant matter, the sloth would have needed to be able to consume a high quantity of food with little precision.

The species would dig for its food, and would have accidentally ingested a large amount of gritty dirt and soil particulate. This gives them a large crown height, called hypsodonty, that is unsuitable for strong bite forces.

The pursuit of bulk plant matter is reflected in the stance, movement, and total bone structure of the ground sloth. In order to dislodge a large amount of foliage from the earth, L. armatus would have used its flat, spade-like phalanges in a hook-and-pull fashion to turn over soil and vegetation. Once again, the evolutionary design of the giant sloth favors quantity and force to quality and speed in its manus.

While the giant sloth was not fully bipedal, its forelimbs show evolutionary pressure for specialized functions over walking and could easily shift its center of gravity. Energy storage is possible in the tendons of the triceps, produces power necessary to execute the digging behavior Lestodon armatus uses to acquire the bulk of its diet.

Extant related species of the magnorder Xenarthra, like anteaters, show a similar design.

Payment

You may use multiple payment methods to buy image such as credit cards, PayPal and bank transfer.

Lestodon (†Lestodon (Gervais 1855))

Order: Pilosa

Family: †Mylodontidae

Temporal range: during the Early Pliocene-Pleistocene (South America, ~5.332–0.012 Ma)

Dimensions: length -4,6 m, height - 170 сm, weight - 2590 kg

A typical representative: † Lestodon armatus (Gervais 1855)

Lestodon is an extinct genus of megafaunal ground sloth from South America during the Pliocene to Pleistocene periods. Its fossil remains have been found in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Brazil. It was a herbivore and primarily fed on the grasses on the South American plains and is thought to perhaps have used its semi-bipedal stance to obtain foliage from trees.

The skeleton morphologically reflects its evolutionary history as well as its daily activities. The skull is two to three orders of magnitude larger than that of living species of sloth, but the muzzle itself shows highly positive allometry to the size of the skull in comparison to modern sloths and even other megafauna of the same order Pilosa.

L. armatus had a large, blunt, and square mandible well adapted for foliage consumption. Its muzzle and dentition show a significant adaptation to this diet. The shape of the muzzle aided the ground sloth in the grazing necessary to sustain the metabolic activity of its large body; square, flat muzzles are associated with bulk feeders while pointed snouts are adaptive features of precision eaters, like the long sloping snout of modern anteaters, which are also in the same class Xenarthra. To sustain its caloric needs with only plant matter, the sloth would have needed to be able to consume a high quantity of food with little precision.

The species would dig for its food, and would have accidentally ingested a large amount of gritty dirt and soil particulate. This gives them a large crown height, called hypsodonty, that is unsuitable for strong bite forces.

The pursuit of bulk plant matter is reflected in the stance, movement, and total bone structure of the ground sloth. In order to dislodge a large amount of foliage from the earth, L. armatus would have used its flat, spade-like phalanges in a hook-and-pull fashion to turn over soil and vegetation. Once again, the evolutionary design of the giant sloth favors quantity and force to quality and speed in its manus.

While the giant sloth was not fully bipedal, its forelimbs show evolutionary pressure for specialized functions over walking and could easily shift its center of gravity. Energy storage is possible in the tendons of the triceps, produces power necessary to execute the digging behavior Lestodon armatus uses to acquire the bulk of its diet.

Extant related species of the magnorder Xenarthra, like anteaters, show a similar design.

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)