Homotherium venezuelensis

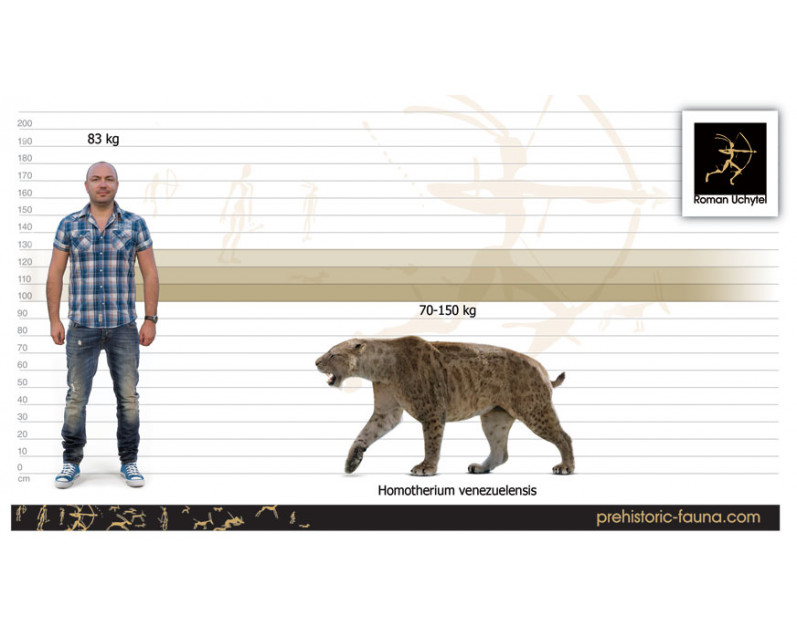

210210Homotherium venezuelensis (Homotherium Fabrini, 1890)

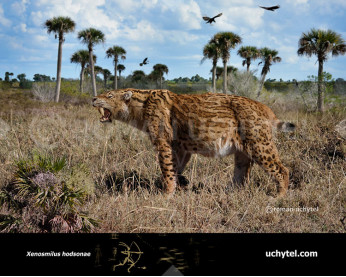

Xenosmilus venezuelensis

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Subfamily: †Machairodontinae

Time period: lived in South America during the early Pleistocene (1.8 million years ago)

Size: 1.5 m in length, 75 cm in height, 100-150 kg of weight.

The remains of an ancient scimitar cat—a relative of the mighty Ice Age predator, the sabertooth—have been found lodged in a tar pit in eastern Venezuela, scientists say. The fierce hunter was found alongside more than 33 species of ancient animals that date back 1.8 million years, to the early Pleistocene.

The scimitar cat and several of the species have never before been found in South America. Along with six scimitar cat jaws and one skull, unprecedented finds include a type of tapir; a tooth that belonged to a spider monkey; and two species of glyptodons, large armored animals related to armadillos.

Ascanio Rincon, the site's lead researcher and a paleontologist at the state-run Venezuelan Scientific Research Institute, hopes the specimens, found in 2006, will help reconstruct the ecology and animal behavior during the early Pleistocene. The find may also reveal the migration of North American and South American plants and animals that took place two to three million years ago when the two continents unified, scientists say. "The fossil record of animals in this period in northern South America is very poor," Rincon said. "The deposit could teach us a great deal about [ancient migrations] particularly here at the door of entry."

Death Traps

Tar pits form when fault lines or porous rocks allow underground pressure to push oil up from the subsoil onto the surface, Rincon said. During the rainy season, puddles form and vegetation takes root, attracting animals, their predators and, later, scavengers that get trapped in the tar and die.The ancient environment at the tar pit was likely similar to today—one of hot savannas and scattered trees, he added. Duck and heron fossils found at the site suggest water was close by, and ancient horse and llama remains indicate a plains environment existed not too far away.

Scimitar Clues

After finding two sabertooth teeth on separate digs in western Venezuela, Rincon guessed that there had to be a scimitar cat fossil in the country. The scimitar, about the size of a modern lion, is a lesser known type of saber-toothed cat that roamed North America during the Ice Age. The hunter used its serrated teeth—shorter than the sabertooth's—to take down mammoths and other prey. The rare scimitar skull suggests the cats had shorter faces than was previously thought, Rincon said. The points where the cat's neck muscles connected to the head also suggested the animal had a more robust neck and a more mobile head, Rincon said. And instead of four holes for the nerves, the newfound scimitar skull has only three. The missing nerve hole perhaps broke off or remains covered up by asphalt, Rincon said, but he is nevertheless excited by the uncertainty. Rincon plans to determine the diet and mobility of these animals to reconstruct their communities. Analyzing the isotopes—or different types of an element—in the fossilized bones will indicate roughly what those animals ate. For instance, he can determine which cats were hunters and which couldn't hunt because of some physical handicap. One intriguing, heavily eroded tooth suggests its owner could not hunt and thus depended on its kin for assistance, Rincon said. Comparing diet and clues such as the eroded tooth with modern tiger communities may also offer insights into ancient scimitar cat populations.

Homotherium venezuelensis (Homotherium Fabrini, 1890)

Xenosmilus venezuelensis

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Subfamily: †Machairodontinae

Time period: lived in South America during the early Pleistocene (1.8 million years ago)

Size: 1.5 m in length, 75 cm in height, 100-150 kg of weight.

The remains of an ancient scimitar cat—a relative of the mighty Ice Age predator, the sabertooth—have been found lodged in a tar pit in eastern Venezuela, scientists say. The fierce hunter was found alongside more than 33 species of ancient animals that date back 1.8 million years, to the early Pleistocene.

The scimitar cat and several of the species have never before been found in South America. Along with six scimitar cat jaws and one skull, unprecedented finds include a type of tapir; a tooth that belonged to a spider monkey; and two species of glyptodons, large armored animals related to armadillos.

Ascanio Rincon, the site's lead researcher and a paleontologist at the state-run Venezuelan Scientific Research Institute, hopes the specimens, found in 2006, will help reconstruct the ecology and animal behavior during the early Pleistocene. The find may also reveal the migration of North American and South American plants and animals that took place two to three million years ago when the two continents unified, scientists say. "The fossil record of animals in this period in northern South America is very poor," Rincon said. "The deposit could teach us a great deal about [ancient migrations] particularly here at the door of entry."

Death Traps

Tar pits form when fault lines or porous rocks allow underground pressure to push oil up from the subsoil onto the surface, Rincon said. During the rainy season, puddles form and vegetation takes root, attracting animals, their predators and, later, scavengers that get trapped in the tar and die.The ancient environment at the tar pit was likely similar to today—one of hot savannas and scattered trees, he added. Duck and heron fossils found at the site suggest water was close by, and ancient horse and llama remains indicate a plains environment existed not too far away.

Scimitar Clues

After finding two sabertooth teeth on separate digs in western Venezuela, Rincon guessed that there had to be a scimitar cat fossil in the country. The scimitar, about the size of a modern lion, is a lesser known type of saber-toothed cat that roamed North America during the Ice Age. The hunter used its serrated teeth—shorter than the sabertooth's—to take down mammoths and other prey. The rare scimitar skull suggests the cats had shorter faces than was previously thought, Rincon said. The points where the cat's neck muscles connected to the head also suggested the animal had a more robust neck and a more mobile head, Rincon said. And instead of four holes for the nerves, the newfound scimitar skull has only three. The missing nerve hole perhaps broke off or remains covered up by asphalt, Rincon said, but he is nevertheless excited by the uncertainty. Rincon plans to determine the diet and mobility of these animals to reconstruct their communities. Analyzing the isotopes—or different types of an element—in the fossilized bones will indicate roughly what those animals ate. For instance, he can determine which cats were hunters and which couldn't hunt because of some physical handicap. One intriguing, heavily eroded tooth suggests its owner could not hunt and thus depended on its kin for assistance, Rincon said. Comparing diet and clues such as the eroded tooth with modern tiger communities may also offer insights into ancient scimitar cat populations.

-797x638.jpg)

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)