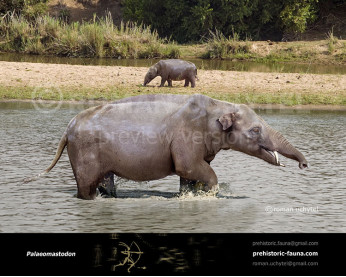

Mammut americanum

134134American mastodon (Mammut americanum Blumenbach, 1799)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Mammutidae

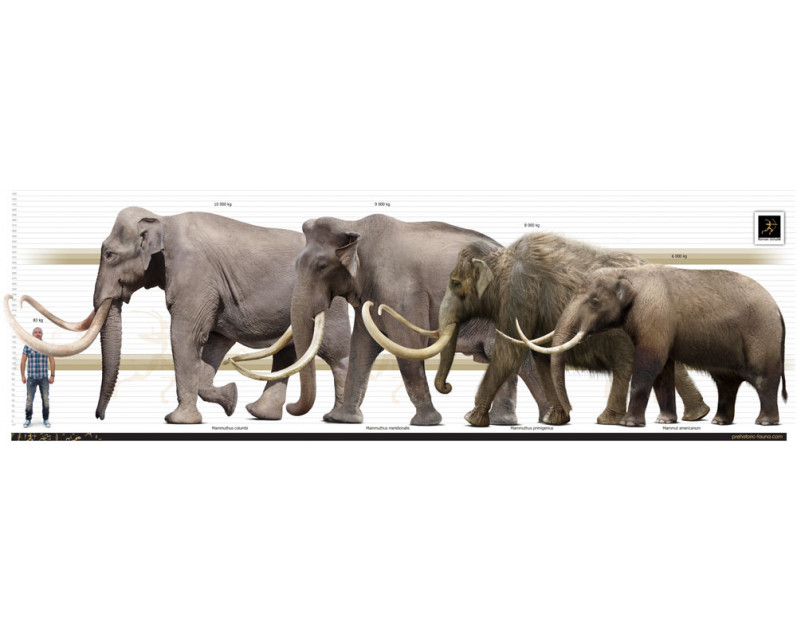

Dimensions: length - 4,5 m, height - 3 m, weight - 6000 kg

Expansion: Pliocene through to the end of the Pleistocene (North America)

The American mastodon resembled a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) in appearance, with a thick coat of shaggy hair. A few skeletons have been found with the fur still attached; examination of the hair suggests that mastodons lacked the undercoat characteristic of mammoths. It was about 3 metres in height at the shoulder and reached a weight of about 6 tons (5443 kg), also similar to woolly mammoths.

However, there are number of significant skeletal differences between mastodons and mammoths. Mastodons' teeth differ dramatically from those of members of the elephant family; they had blunt, conical, nipple-like projections on the crowns of their molars, which were more suited to chewing leaves than the high-crowned teeth mammoths used for grazing; the name mastodon (or mastodont) means "nipple teeth" and is also an obsolete name for their genus. Their skulls are larger and flatter than those of mammoths, while their skeleton is stockier and more robust.

The tusks of the American mastodon sometimes exceeded five metres in length; they curved upwards, but less dramatically than those of the woolly mammoth. Young males had vestigial lower tusks that were lost in adulthood. However, it has been proven that female mastodons had lower pairs of tusks. The tusks were probably used to break branches and twigs, although some evidence suggests males may have used them in mating challenges; one tusk is often shorter than the other, suggesting that, like humans and modern elephants, mastodons may have had laterality Examination of fossilized tusks revealed a series of regularly spaced shallow pits on the underside of the tusks. Microscopic examination showed damage to the dentin under the pits. It is theorized that the damage was caused when the males were fighting over mating rights. The curved shape of the tusks would have forced them downward with each blow, causing damage to the newly forming ivory at the base of the tusk. The regularity of the damage in the growth patterns of the tusks indicates that this was an annual occurrence, probably occurring during the spring and early summer.

American mastodon (Mammut americanum Blumenbach, 1799)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Mammutidae

Dimensions: length - 4,5 m, height - 3 m, weight - 6000 kg

Expansion: Pliocene through to the end of the Pleistocene (North America)

The American mastodon resembled a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) in appearance, with a thick coat of shaggy hair. A few skeletons have been found with the fur still attached; examination of the hair suggests that mastodons lacked the undercoat characteristic of mammoths. It was about 3 metres in height at the shoulder and reached a weight of about 6 tons (5443 kg), also similar to woolly mammoths.

However, there are number of significant skeletal differences between mastodons and mammoths. Mastodons' teeth differ dramatically from those of members of the elephant family; they had blunt, conical, nipple-like projections on the crowns of their molars, which were more suited to chewing leaves than the high-crowned teeth mammoths used for grazing; the name mastodon (or mastodont) means "nipple teeth" and is also an obsolete name for their genus. Their skulls are larger and flatter than those of mammoths, while their skeleton is stockier and more robust.

The tusks of the American mastodon sometimes exceeded five metres in length; they curved upwards, but less dramatically than those of the woolly mammoth. Young males had vestigial lower tusks that were lost in adulthood. However, it has been proven that female mastodons had lower pairs of tusks. The tusks were probably used to break branches and twigs, although some evidence suggests males may have used them in mating challenges; one tusk is often shorter than the other, suggesting that, like humans and modern elephants, mastodons may have had laterality Examination of fossilized tusks revealed a series of regularly spaced shallow pits on the underside of the tusks. Microscopic examination showed damage to the dentin under the pits. It is theorized that the damage was caused when the males were fighting over mating rights. The curved shape of the tusks would have forced them downward with each blow, causing damage to the newly forming ivory at the base of the tusk. The regularity of the damage in the growth patterns of the tusks indicates that this was an annual occurrence, probably occurring during the spring and early summer.

-797x638.jpg)

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

-2015-346x277.jpg)