Marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex)

5151Marsupial lion (Thylacoleo Owen, 1859)

Order: Diprotodontia

Family: †Thylacoleonidae

Dimensions: length - 1,5 m, height - 80 сm, weight -130 kg

Temporal range: lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the late Pleistocene (2 million to 30 thousand years ago)

A typical representative: Thylacoleo carnifex Owen, 1859

The marsupial lion is the largest meat-eating mammal known to have ever existed in Australia, and one of the largest marsupial carnivores from anywhere in the world (although see Thylacosmilus and Borhyaena). Individuals ranged up to around 75 cm high at the shoulder and about 150 cm from head to tail. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show that they averaged 100 to 130 kg in weight although individuals heavier than 160 kg may not have been uncommon. This would make it quite comparable to female lions and tigers in general size.

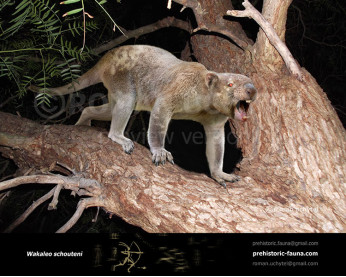

The animal was extremely robust with powerfully built jaws and very strong forelimbs. It possessed retractable claws, a unique trait among marsupials. This would have allowed the claws to remain sharp by protecting them from being worn down on hard surfaces. The claws were well-suited to securing prey and for climbing trees. The first digits ("thumbs") on each hand were semi-opposable and bore an enlarged claw. Palaeontologists believe that this would have been used to grapple with and slash at its intended prey as well as providing it with a sure footing on tree trunks and branches. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing. It is unclear whether the marsupial lion exhibited syndactyly (fused second and third toes) like other diprotodonts.

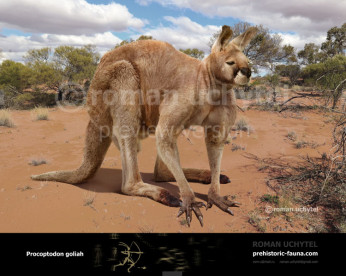

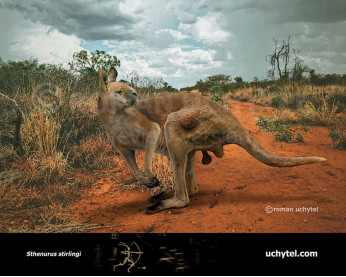

The marsupial lion's hindquarters were also well-developed although to a lesser extent than the front of the animal. Remains of the animal show that it had a relatively thick and strong tail and that the vertebrae possessed chevrons on their undersides where the tail would have contacted the ground. These would have served to protect critical elements such as nerves and blood vessels if the animal used its tail to support itself when on its hind legs, much like present day kangaroos do. Taking this stance would free up its forelimbs to tackle or slash at its intended victim.

Marsupial lion (Thylacoleo Owen, 1859)

Order: Diprotodontia

Family: †Thylacoleonidae

Dimensions: length - 1,5 m, height - 80 сm, weight -130 kg

Temporal range: lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the late Pleistocene (2 million to 30 thousand years ago)

A typical representative: Thylacoleo carnifex Owen, 1859

The marsupial lion is the largest meat-eating mammal known to have ever existed in Australia, and one of the largest marsupial carnivores from anywhere in the world (although see Thylacosmilus and Borhyaena). Individuals ranged up to around 75 cm high at the shoulder and about 150 cm from head to tail. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show that they averaged 100 to 130 kg in weight although individuals heavier than 160 kg may not have been uncommon. This would make it quite comparable to female lions and tigers in general size.

The animal was extremely robust with powerfully built jaws and very strong forelimbs. It possessed retractable claws, a unique trait among marsupials. This would have allowed the claws to remain sharp by protecting them from being worn down on hard surfaces. The claws were well-suited to securing prey and for climbing trees. The first digits ("thumbs") on each hand were semi-opposable and bore an enlarged claw. Palaeontologists believe that this would have been used to grapple with and slash at its intended prey as well as providing it with a sure footing on tree trunks and branches. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing. It is unclear whether the marsupial lion exhibited syndactyly (fused second and third toes) like other diprotodonts.

The marsupial lion's hindquarters were also well-developed although to a lesser extent than the front of the animal. Remains of the animal show that it had a relatively thick and strong tail and that the vertebrae possessed chevrons on their undersides where the tail would have contacted the ground. These would have served to protect critical elements such as nerves and blood vessels if the animal used its tail to support itself when on its hind legs, much like present day kangaroos do. Taking this stance would free up its forelimbs to tackle or slash at its intended victim.

1-797x638.jpg)

3-797x638.jpg)

-797x638.jpg)

1-70x56.jpg)

3-70x56.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

1-346x277.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)