Palaeopropithecus

286286Palaeopropithecus († Palaeopropithecus ingens Grandidier, 1899)

Order: Primates

Suborder: Strepsirrhini

Family: †Palaeopropithecidae

Temporal range: during the Late Pliocene - Holocene (Madagascar)

Dimensions: weight - 40-60 kg

A typical representative: Palaeopropithecus ingens Grandidier, 1899

Palaeopropithecus was one of three recently extinct genera of sloth lemur that was found on Madagascar, and were closely related to living lemur species found there today. There were three known species, Palaeopropithecus ingens, P. maximus, and P. kelyus. New radiocarbon dates indicate that these large sloth lemurs may have still been living around 1500 CE.

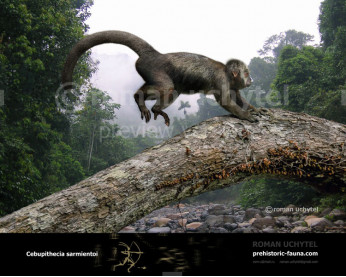

Palaeopropithecus primarily lived in the trees to stay away from predators as well as to gain valuable resources in food and shelter. To survive properly in the trees, Palaeopropithecus had long and powerful arms and legs, each with significantly long fingers and toes to allow them to hang upside down on trees. These were used to swing from branch to branch to travel across the jungle. These long arms made it much easier to grab hold of various trees and branches, making travel at the arboreal level easier. Laurie Godrey stated in The Extinct Sloth Lemurs of Madagascar, "Thus, these animals exhibit the odd behavioral combination of being both specialized leapers and adept climbers and hangers." The long arms of Palaeopropithecus had hook like extremities on their hands and feet. This benefited Palaeopropithecus by enabling them to hook their bodies onto the foliage to stabilize themselves as they traversed through the trees. Palaeopropithecus on average weighed between 40-60 kg. This weight is heavier than most modern lemurs and could potentially have caused the species to fall while hanging on branches, forcing the species to make sufficient use of their long arms and legs to survive. Palaeopropithecus eating habits were different then modern lemurs. The teeth of Palaeoprophithecus indicate that the animal was folivorous to eat leaves and tougher so they can eat hard foods such as nuts and seeds. This helped them fill out a generalized niche where they had multiple food resources to rely on.

The anatomy of their bones were generally curved with a sixty-degree bend on major bones in the legs and arms. These bones were much denser than normal and with the edition of the curved structure of the bones it allowed Palaeopropithecus an easier capability to swing from branch to branch. William Junger wrote, “curvature indicates that the sloth lemurs are one of the most suspensory clades of mammals ever to evolve. The curved bones also helped them gain more torque and speed allowing them to reach branches at great distances. This was because they had more muscle to hold onto various branches and trees. The relatively small body of Palaeopropithecus, while large compared to the modern lemur, had a great degree curve because it was smaller in stature. There is an inverse relationship between the bigger the animal and the smaller the bone degree curve.

Biomechanical theory suggests that bone curvature in Palaeopropithecus hand bones is linked to the functional demands of the organisms environment. In other words, the unique functional morphology of the Palaeopropithecus finger bones is a result of the environment in which it lived. This is because curved phalanges, such as the phalanges of Palaeopropithecus, are commonly associated with the gripping function needed to survive in an arboreal habitat.

When Palaeopropithecus went extinct is not exactly clear, however scientists have suggested that it could be as recent as about five hundred years ago (anywhere from 1300 to 1620AD). The reason behind the extinction of the several species of Palaeopropithecus has been attributed to the presence of humans to the island of Madagascar, the earliest evidence of which dates back to 2325±43 yr BP. Scientists have found fossils of Palaeopropithecus that appeared to have cut marks in them, suggesting flesh removal with a sharp object, indicating that the species was hunted by the earliest colonists to the island of Madagascar as a source for food. The first evidence of the early human butchery to Palaeopropithecus was found by Hon. Paul Ayshford Methuen, in 1911, who traveled to Madagascar expressly to collect bones of the extinct lemurs for the Oxford Museum. The slow locomotion habits of Palaeopropithecus likely made them an easy target for their human predators, who would consume them for food, as well as use the bones for tools. Along with being relatively large, these lemurs became targets because they were active during the day as were humans. Along with their diurnal nature, another factor that led to their extinction was a slow reproductive rate. They were killed faster than they could reproduce.

The introduction of humans to Madagascar brought change to an island that had yet to experience the lifestyles of human beings. Some believe that hunting was not the only problem brought to Madagascar by humans. There is a possibility that humans bringing over livestock may have affected some species. Although it would not have been disastrous, it could have finished off some species. Just a small amount of competition could offset the balance of an ecosystem.

Palaeopropithecus († Palaeopropithecus ingens Grandidier, 1899)

Order: Primates

Suborder: Strepsirrhini

Family: †Palaeopropithecidae

Temporal range: during the Late Pliocene - Holocene (Madagascar)

Dimensions: weight - 40-60 kg

A typical representative: Palaeopropithecus ingens Grandidier, 1899

Palaeopropithecus was one of three recently extinct genera of sloth lemur that was found on Madagascar, and were closely related to living lemur species found there today. There were three known species, Palaeopropithecus ingens, P. maximus, and P. kelyus. New radiocarbon dates indicate that these large sloth lemurs may have still been living around 1500 CE.

Palaeopropithecus primarily lived in the trees to stay away from predators as well as to gain valuable resources in food and shelter. To survive properly in the trees, Palaeopropithecus had long and powerful arms and legs, each with significantly long fingers and toes to allow them to hang upside down on trees. These were used to swing from branch to branch to travel across the jungle. These long arms made it much easier to grab hold of various trees and branches, making travel at the arboreal level easier. Laurie Godrey stated in The Extinct Sloth Lemurs of Madagascar, "Thus, these animals exhibit the odd behavioral combination of being both specialized leapers and adept climbers and hangers." The long arms of Palaeopropithecus had hook like extremities on their hands and feet. This benefited Palaeopropithecus by enabling them to hook their bodies onto the foliage to stabilize themselves as they traversed through the trees. Palaeopropithecus on average weighed between 40-60 kg. This weight is heavier than most modern lemurs and could potentially have caused the species to fall while hanging on branches, forcing the species to make sufficient use of their long arms and legs to survive. Palaeopropithecus eating habits were different then modern lemurs. The teeth of Palaeoprophithecus indicate that the animal was folivorous to eat leaves and tougher so they can eat hard foods such as nuts and seeds. This helped them fill out a generalized niche where they had multiple food resources to rely on.

The anatomy of their bones were generally curved with a sixty-degree bend on major bones in the legs and arms. These bones were much denser than normal and with the edition of the curved structure of the bones it allowed Palaeopropithecus an easier capability to swing from branch to branch. William Junger wrote, “curvature indicates that the sloth lemurs are one of the most suspensory clades of mammals ever to evolve. The curved bones also helped them gain more torque and speed allowing them to reach branches at great distances. This was because they had more muscle to hold onto various branches and trees. The relatively small body of Palaeopropithecus, while large compared to the modern lemur, had a great degree curve because it was smaller in stature. There is an inverse relationship between the bigger the animal and the smaller the bone degree curve.

Biomechanical theory suggests that bone curvature in Palaeopropithecus hand bones is linked to the functional demands of the organisms environment. In other words, the unique functional morphology of the Palaeopropithecus finger bones is a result of the environment in which it lived. This is because curved phalanges, such as the phalanges of Palaeopropithecus, are commonly associated with the gripping function needed to survive in an arboreal habitat.

When Palaeopropithecus went extinct is not exactly clear, however scientists have suggested that it could be as recent as about five hundred years ago (anywhere from 1300 to 1620AD). The reason behind the extinction of the several species of Palaeopropithecus has been attributed to the presence of humans to the island of Madagascar, the earliest evidence of which dates back to 2325±43 yr BP. Scientists have found fossils of Palaeopropithecus that appeared to have cut marks in them, suggesting flesh removal with a sharp object, indicating that the species was hunted by the earliest colonists to the island of Madagascar as a source for food. The first evidence of the early human butchery to Palaeopropithecus was found by Hon. Paul Ayshford Methuen, in 1911, who traveled to Madagascar expressly to collect bones of the extinct lemurs for the Oxford Museum. The slow locomotion habits of Palaeopropithecus likely made them an easy target for their human predators, who would consume them for food, as well as use the bones for tools. Along with being relatively large, these lemurs became targets because they were active during the day as were humans. Along with their diurnal nature, another factor that led to their extinction was a slow reproductive rate. They were killed faster than they could reproduce.

The introduction of humans to Madagascar brought change to an island that had yet to experience the lifestyles of human beings. Some believe that hunting was not the only problem brought to Madagascar by humans. There is a possibility that humans bringing over livestock may have affected some species. Although it would not have been disastrous, it could have finished off some species. Just a small amount of competition could offset the balance of an ecosystem.

-346x277.jpg)