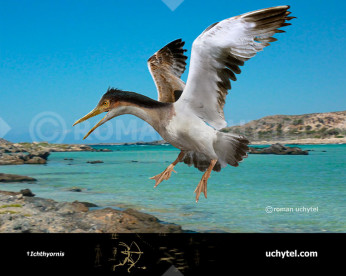

Palaelodus

24412441

Palaelodus (†Palaelodus (Milne-Edwards, 1863))

Class: Aves

Order: Phoenicopteriformes

Family: †Palaelodidae

Time period: Oligocene–Miocene (Pleistocene?)

Size: more than 1,4 m in height, 3,5 kg of weight

Palaelodus is an extinct genus of bird of the Palaelodidae family, distantly related to flamingos. They were slender birds with long, thin legs and a long neck resembling their modern relatives, but likely lived very different livestyles. They had straight, conical beaks not suited for filter feeding and legs showing some similarities to grebes. Their precise lifestyle is disputed, with researchers in the past suggesting they may have been divers, while more recent research suggests they may have used their stiff toes as paddles for swimming while feeding on insect larvae and snails. This behavior may have been key in later phoenicopteriforms developing filterfeeding bills. The genus includes between five and eight species and is found across Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and possibly South America. However some argue that most of the taxa named from Europe simply represent differently sized individuals of one single species. Palaelodus was most abundant during the Late Oligocene to Middle Miocene periods, but isolated remains from Australia indicate that the genus, or at least a relative, survived until the Pleistocene.

In Worthy et al. (2010) it is suggested that palaelodids were wading birds, more akin to flamingos, while publications by Mayr suggest a swimming lifestyle.

These birds may have shown the first signs of becoming filter feeders. Even if a thick tongue was present, Palaelodus would likely not have been able to filter feed in the same manner as adult flamingos. Instead the bill shows greater similarity to those of juvenile flamingos, which have not yet developed this mechanism.

Fossils of Palaelodus are exclusively known from lacustrine environments and the presence of salt glands indicates that regardless of the details of their diet, they must have foraged in saline or at least brackish waters like flamingos. The large number of Palaelodus remains found in certain localities indicates that areas inhabited by this genus were rich in their favored food items. Milne-Edwards proposed that this could contain the larvae of caddisflies and snails, which were particularly abundant at Saint-Gérand-le-Puy. Caddisflies are in fact so common in these early Miocene strata that their casings make up part of the local limestone. It is therefore possible that Palaelodids and related genera were specialised in feeding on small invertebrates and subsequently set the groundwork for the more derived filter feeding apparatus of phoenicopterids.[4]

European Palaelodus species may have lived in large flocks like modern flamingos. Species from Australia and New Zealand meanwhile may have been less social based on the fact that only few bones are known across multiple localities. This case is made partially in light of the palaelodid remains from New Zealand, where fossil ducks are found in abundance likely due to flocking behavior, yet the remains of phoenicopteriforms are rare.

Оплата

У Вас є кілька зручних способів купівлі зображення: кредитна чи дебетова картка Visa, Mastercard, Maestro; PayPal або банківський переказ

Palaelodus (†Palaelodus (Milne-Edwards, 1863))

Class: Aves

Order: Phoenicopteriformes

Family: †Palaelodidae

Time period: Oligocene–Miocene (Pleistocene?)

Size: more than 1,4 m in height, 3,5 kg of weight

Palaelodus is an extinct genus of bird of the Palaelodidae family, distantly related to flamingos. They were slender birds with long, thin legs and a long neck resembling their modern relatives, but likely lived very different livestyles. They had straight, conical beaks not suited for filter feeding and legs showing some similarities to grebes. Their precise lifestyle is disputed, with researchers in the past suggesting they may have been divers, while more recent research suggests they may have used their stiff toes as paddles for swimming while feeding on insect larvae and snails. This behavior may have been key in later phoenicopteriforms developing filterfeeding bills. The genus includes between five and eight species and is found across Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and possibly South America. However some argue that most of the taxa named from Europe simply represent differently sized individuals of one single species. Palaelodus was most abundant during the Late Oligocene to Middle Miocene periods, but isolated remains from Australia indicate that the genus, or at least a relative, survived until the Pleistocene.

In Worthy et al. (2010) it is suggested that palaelodids were wading birds, more akin to flamingos, while publications by Mayr suggest a swimming lifestyle.

These birds may have shown the first signs of becoming filter feeders. Even if a thick tongue was present, Palaelodus would likely not have been able to filter feed in the same manner as adult flamingos. Instead the bill shows greater similarity to those of juvenile flamingos, which have not yet developed this mechanism.

Fossils of Palaelodus are exclusively known from lacustrine environments and the presence of salt glands indicates that regardless of the details of their diet, they must have foraged in saline or at least brackish waters like flamingos. The large number of Palaelodus remains found in certain localities indicates that areas inhabited by this genus were rich in their favored food items. Milne-Edwards proposed that this could contain the larvae of caddisflies and snails, which were particularly abundant at Saint-Gérand-le-Puy. Caddisflies are in fact so common in these early Miocene strata that their casings make up part of the local limestone. It is therefore possible that Palaelodids and related genera were specialised in feeding on small invertebrates and subsequently set the groundwork for the more derived filter feeding apparatus of phoenicopterids.[4]

European Palaelodus species may have lived in large flocks like modern flamingos. Species from Australia and New Zealand meanwhile may have been less social based on the fact that only few bones are known across multiple localities. This case is made partially in light of the palaelodid remains from New Zealand, where fossil ducks are found in abundance likely due to flocking behavior, yet the remains of phoenicopteriforms are rare.

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)