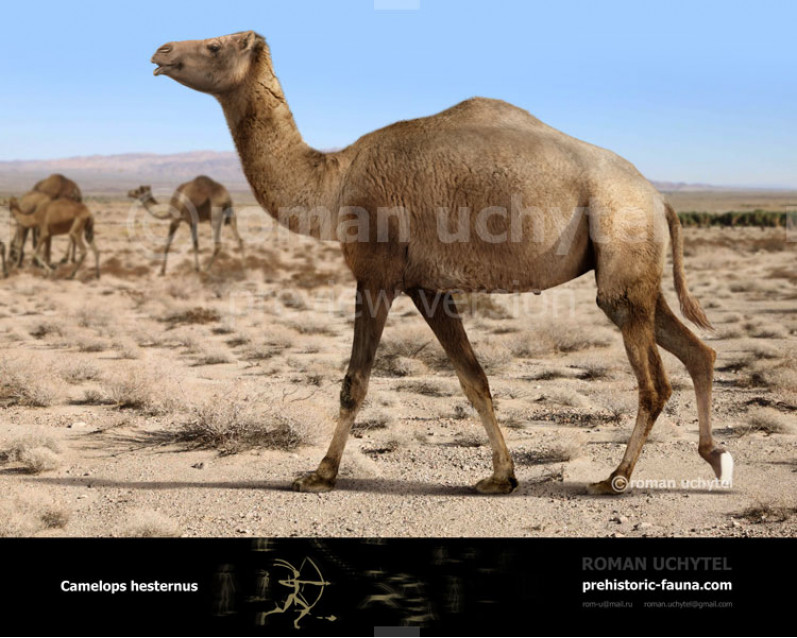

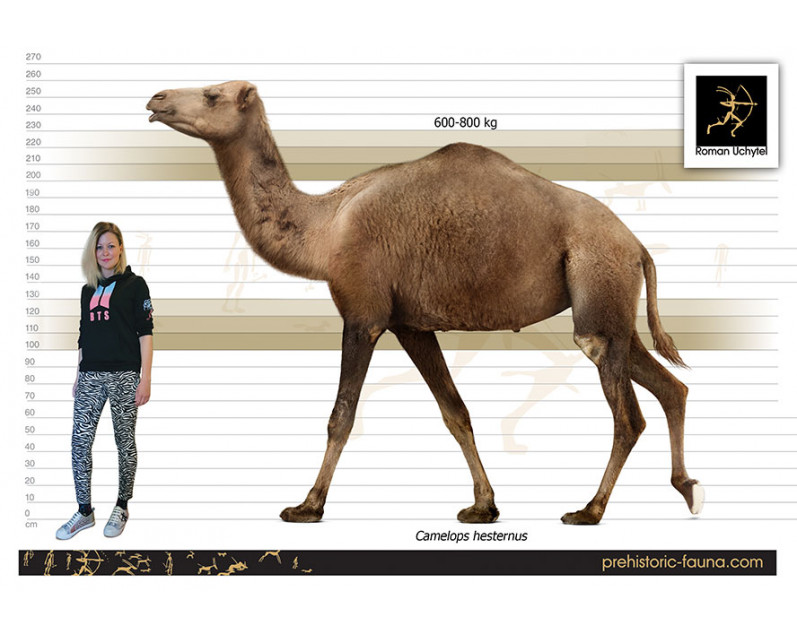

Camelops hesternus (Pleistocene western camel)

312312Camelops, (†Camelops Leidy, 1873)

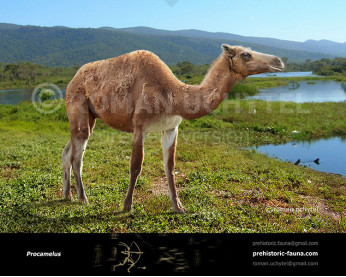

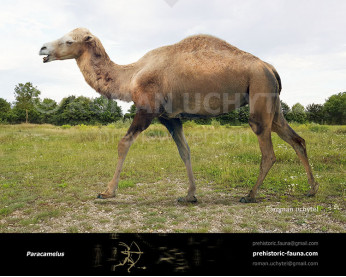

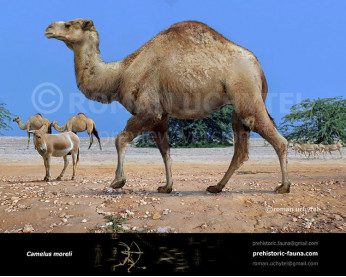

Order: Artiodactyla

Family: Camelidae

Time period: the end of the Pleistocene (North America)

Size: 3,4 m in length, 220 cm in height, 600 - 800 kg of weight

Typical representative: Camelops hesternus

Paleontologists can never completely put their favourite theories about life during the Pleistocene epoch to gentle rest. Ice age creatures have a knack for sowing doubt and sparking debate tens of thousands to millions of years after their deaths. A piece of bone suddenly emerges from Klondike gold-mine muck and comfortable old certainties are thrown into doubt. Or a new technology allows a fossil that had been languishing in a museum drawer for decades to be revisited, redated and redebated. This scientific drama repeatedly flares up over Yukon discoveries, such as horse skulls and mastodon molars. Only this week, another new sediment-shaking paper based on Yukon bones made international news, when Genomic Data from Extinct North American Camelops Revise Camel Evolutionary History was published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Vertebrate paleontologists have something new to argue over. And even those of us trapped in the 21st century are suddenly thrilled by a new image from an old, old North. “I think just the sheer fact that there is something to be learned about camels living in the Arctic or Subarctic definitely captures people’s attention,” says one of the paper’s authors, Yukon paleontologist Grant Zazula. “It doesn’t seem to make sense for camels to be here.” But they were here, and apparently flourishing, before time and climate change took them. When were they roaming Yukon? Radio-carbon dating is only effective up to about 50,000 years ago, says Zazula. Our camel bones are older than that, he adds.

“We have found other camel remains here in the Yukon that stratigraphically say they were here during the last interglacial warm period, between 125,000 and 100,000 years ago… and they probably weren’t here for very long.”

Camelops, (†Camelops Leidy, 1873)

Order: Artiodactyla

Family: Camelidae

Time period: the end of the Pleistocene (North America)

Size: 3,4 m in length, 220 cm in height, 600 - 800 kg of weight

Typical representative: Camelops hesternus

Paleontologists can never completely put their favourite theories about life during the Pleistocene epoch to gentle rest. Ice age creatures have a knack for sowing doubt and sparking debate tens of thousands to millions of years after their deaths. A piece of bone suddenly emerges from Klondike gold-mine muck and comfortable old certainties are thrown into doubt. Or a new technology allows a fossil that had been languishing in a museum drawer for decades to be revisited, redated and redebated. This scientific drama repeatedly flares up over Yukon discoveries, such as horse skulls and mastodon molars. Only this week, another new sediment-shaking paper based on Yukon bones made international news, when Genomic Data from Extinct North American Camelops Revise Camel Evolutionary History was published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Vertebrate paleontologists have something new to argue over. And even those of us trapped in the 21st century are suddenly thrilled by a new image from an old, old North. “I think just the sheer fact that there is something to be learned about camels living in the Arctic or Subarctic definitely captures people’s attention,” says one of the paper’s authors, Yukon paleontologist Grant Zazula. “It doesn’t seem to make sense for camels to be here.” But they were here, and apparently flourishing, before time and climate change took them. When were they roaming Yukon? Radio-carbon dating is only effective up to about 50,000 years ago, says Zazula. Our camel bones are older than that, he adds.

“We have found other camel remains here in the Yukon that stratigraphically say they were here during the last interglacial warm period, between 125,000 and 100,000 years ago… and they probably weren’t here for very long.”

-797x638.jpg)

-797x638.jpg)

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)